Remark to the title[1]

Verstecke sind unzählige, Rettung nur eine, aber Möglichkeiten der Rettung wieder so viele wie Verstecke. Es gibt ein Ziel, aber keinen Weg; was wir Weg nennen, ist Zögern.

Franz Kafka[2]

Dann erst wird man mit Sicherheit erkennen, daß Kafkas ganzes Werk einen Kodex von Gesten darstellt, die keineswegs von Hause aus für den Verfasser eine sichere symbolische Bedeutung haben, vielmehr in immer wieder anderen Zusammenhängen und Versuchsanordnungen um eine solche angegangen werden. Das Theater ist der gegebene Ort solcher Versuchsanordnungen.

Walter Benjamin[3]

The Hebrew Notebook – And other stories by Franz Kafka[4] is a performance of the Ruth Kanner Theatre Group inspired by the notebook that Kafka used for studying Hebrew which is kept in the Israel National Library in Jerusalem.[5] The performance premiered in November 2013 as part of the 120th anniversary celebrations of the library for which twelve Israeli artists had been invited to create a work of art connected to the library or based on any of its holdings, and it is still (as I am writing this in March 2016) occasionally performed, mainly at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art as well as in other venues. It was also invited to participate in the symposium on Kafka and the Theatre at the Goethe University in Frankfurt am Main, in December 2014 and was shown twice at the Künstlerhaus Mousonturm for an audience, most of which without any knowledge of Hebrew. In this version, German (together with English, because the actors are not German speakers) was much more prominent than in the ‚original‘ Israeli/Hebrew version of the performance.

According to their website the Ruth Kanner Theatre Group „has been engaged since 1998 in exploring its own surroundings by searching for a local theatrical language, interweaving storytelling, physical theater and visual imagery. The group’s re-examination of Israeli narratives is performed through literary and documentary texts, creating Storytelling Theater.“[6] The group has a clearly pronounced avant-garde agenda both in terms of the form and the contents of their productions, collectively telling a story where each actor either appears as ‚her‘- or ‚him‘-self or displays several ‚figures‘, swiftly shifting the focus or the character by presenting short ’sketches‘ rather than staging dramatic texts with the actors impersonating (or representing) fully ‚visible‘ characters.

The virtuosity of the individual actors as well as their highly synchronized, choreographic and vocal expressivity as a chorus and individually – always drawing attention to the language and the individual words of the text – serve as the common basis for the group’s ongoing critical examination of fundamental ideological concerns in today’s Israeli society. The Hebrew Notebook – And other stories by Franz Kafka is no exception. All the actors have studied in the Department of Theatre Arts at Tel Aviv University, where the director of the group, Ruth Kanner holds a position as professor in acting and ’scenic expression‘.[7]

The performance consists of two main sections telling at least three different ’stories‘. The first part reveals the story how the director first learned about Kafka’s Hebrew notebook and presents short fragments which in retrospect can be seen as a documentation of the preparations and the rehearsals for the performance. It takes place in a ‚white box‘ gallery space where the spectators are invited to observe or listen to different exhibits, mainly presented by the individual actors but can also watch pictures or texts that are mounted on the walls. The second part of the performance takes place in a traditional performance space with a stage and a few rows of chairs for the spectators. It presents two distinct kinds of ’stories‘. First the actors simply recite the words in the notebook, mostly in Hebrew but also with some words in German[8], and then they ‚tell‘ a few of Kafka’s own stories (in their own typical form of collective narration), demonstrating how many of the words from the notebook (or their ‚atmosphere‘ or ‚gestures‘) have been central for Kafka’s own writing and appear in his ‚other‘ stories from the period when he studied Hebrew – like An Old Manuscript (Ein altes Blatt) and Jackals and Arabs (Schakale und Araber) which were both published, though not for the first time, in the collection of stories A Country Doctor (Ein Landarzt) published in 1919. There is also a short ritual transition between the two parts when the spectators walk through the door from the gallery into the more traditional performance space. The most prominent impression that remains after having seen the performance is that even if the Hebrew words Kafka studied and wrote down in his notebook and their translations into German, as well as the notebook itself (as a specific highly valued ‚object‘ in the library archive), through which the actors gradually begin to explore the enigmatic mysteries of Kafka’s unique fictional universe, what they actually discover (and show us) is much more complicated and more monstrous than the first, even somewhat naive steps of learning a new language.

At the same time as the performance presents the story of Kafka’s Hebrew studies it implicitly also tells the larger story of the revival of Hebrew as an everyday language, which was an important part of the Zionist project, starting already during the last decade of the 19th century with the establishment of the Hebrew Language Committee in Jerusalem in 1890. Kafka, who only wrote in German, began studying Hebrew in 1917, the year he was diagnosed with tuberculosis and continued these studies – with interruptions and with three different teachers – until a few months before his death, in June 1924. At this time, the utopian dream of a Jewish homeland where Hebrew will be spoken had become more real, after the British army – during the First World War – had conquered what they termed Mandatory Palestine (parts of which became the State of Israel in 1948) from the crumbling Ottoman Empire and issued the Balfour Declaration favoring „the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people“[9] in 1917, the year Kafka began his Hebrew studies.

The performance of The Hebrew Notebook – And other stories by Franz Kafka in effect also shows that this utopian dream, which Kafka participated in by studying Hebrew (and at some moments in his life even considered to take an active part in), has now (for many of the spectators) been transformed into a dystopian nightmare, as depicted by Kafka in his writings. The performance even suggests that Kafka was able to write his nightmarish stories because he sensed that there is something inherently fated or threatening in a national project where the Hebrew language will actually be spoken. Approximately 10 years later Gershom Scholem expresses this in a letter to Franz Rosenzweig.[10] The performance has also been shown at a time when the legal disputes over the ownership of the Kafka manuscripts which had been brought to Mandatory Palestine by Kafka’s close friend Max Brod who fled from Prague in 1939 were frequently reported in the daily press.[11]

The Hebrew Notebook

The notebook is in effect Kafka’s private dictionary containing the Hebrew words he was learning and their German counterparts. All the words in the notebook, in both languages, are in Kafka’s own handwriting, written down with a pencil in large letters and with much more space around the individual words than in most of his preserved letters, diaries or literary manuscripts. Maybe this reflects Kafka’s position as a ‚pupil‘ studying the Hebrew words, literally ‚making room‘ for them, also enabling him to reflect on each individual word, separately. It is however not possible to say with any certainty in which language a particular word originated, with the German words (written from left to right) or the Hebrew words (from right to left) on the pages of the notebook with the two languages, approaching each other from the margins of each of the two columns of words, keeping a safe distance between them.[12]

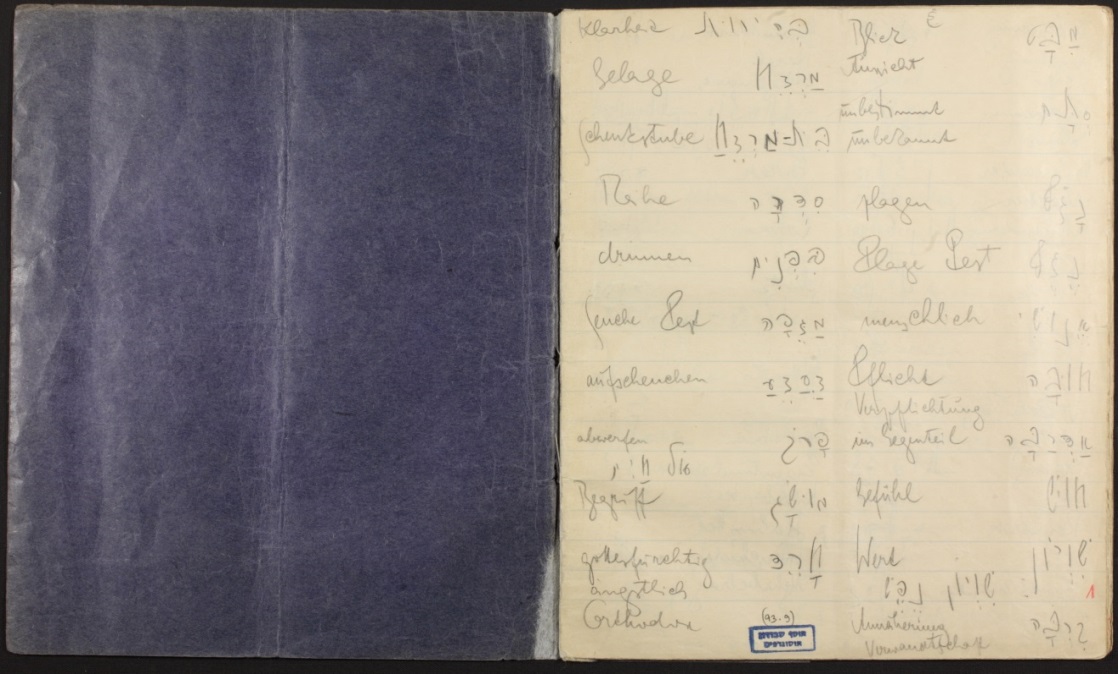

Fig. 1 The first page of the Hebrew Notebook, beginning (in the upper right hand corner) with the Hebrew word מבט (Mabat) translated as Blick and Ansicht. This is also the first word the actors read from the notebook in the second part of the performance.

Today we can only speculate how the notebook itself originated with Kafka and his teacher – who for the notebook in the archives of the Israel National Library was Puah (Menczel) Ben-Tovim (1903-1991) – probably conducting conversations in Hebrew about the meanings of the Hebrew words. It is also possible that they read a text in Hebrew together and we know that Kafka also used the Hebrew textbook The language of our people by Moshe Rat for his studies, which could also have been a possible source for the words in Kafka’s notebook.[13] At some point Kafka could make himself more or less fully understood in Hebrew; a letter he wrote in Hebrew to Puah (Menczel) Ben-Tovim has been preserved.[14]

The notebook contains the potentials for many forms of performativity which have been developed and interwoven into the performance. Reading the notebook as a document based on Hebrew, from right to left, the first word in the notebook is מבט (mabat), which Kafka has noted down on the top of the right hand column of the first page and translates as Blick meaning ‚view‘, ‚glance, ‚gaze‘, or Ansicht which is somewhat more abstract, meaning ‚idea‘, ’notion‘, ‚judgement‘. If we read the notebook on the basis of German, from left to right on the page, the first word in the notebook on the top of the left column is Klarheit, which in Hebrew is בהירות (behirut), meaning clarity or lucidity. Looking at the page in the notebook the way in which the words in the first row have been noted down, with behirut almost pushed off the page by the following word which is Gelage, in Hebrew מרזח (marzeach), meaning ‚feast‘ of ‚banquet‘ indicates that it is perhaps a later addition or an afterthought.

In spite of the fact that the notebook opens as a book written with Latin letters, opening the cover page to the left with the back cover of the book on the right (and not as a Hebrew book, with the back cover on the left) the second part of the performance begins by giving precedence to the way in which a page is read in Hebrew, beginning in the upper right hand corner of the page. The reading of the notebook begins with Tali Kark somewhat hesitantly pronouncing the word מבט (mabat; as ma-bat), initiating the spectators into the inner secrets of the notebook by establishing a ‚gaze‘ and transforming the word on the page which is simultaneously screened on the wall behind the actors into the very performance we are watching. This initiation is followed by the Hebrew word סתם (stam), the second word in the right column on the page which Kafka translated as unbestimmt, meaning ‚indecisive‘. In today’s Hebrew the word stam refers to something which has no particular reason.

The Hebrew Notebook – And other stories by Franz Kafka presents a broad range of associative strategies by creating a labyrinthine ‚word-scape‘, offering suggestions what the words that Kafka studied ‚mean‘, also showing how many of them have ‚invaded‘ his writings or appear in the performance as distant echoes emerging from his texts. The suggestive evocations of the words open up new venues for understanding Kafka’s texts, even if the performativity connected to them can only begin to decipher their enigmas, barely letting us peep below the surface. And as is always the case with enigmatic texts that present a ‚riddle‘, when we have (or think we have) found a solution, we immediately realize that it is only a temporary resting-place, compelling us to continue searching for new answers. But what we can gain in cases like this is that the contours of enigma become more distinctly visible and get a clearer formulation by this process.

What the performance also makes us realize is that Kafka’s texts, as Benjamin suggested in his essay published on the tenth anniversary of Kafka’s death – quoted as the second motto above and presented as an exhibit on the wall in the first part of the performance – constitute a „code of gestures which surely had no definite symbolic meaning for the author from the outset; rather, the author tried to derive such a meaning from them in ever-changing contexts and experimental groupings.“[15] This means that Kafka himself was also searching for the symbolic meaning of the „code of gestures“ inscribed in his writings. And following Benjamin’s directive, the Ruth Kanner Theatre Group shows us that their performance continues Kafka’s own efforts to derive the meaning from these gestures (as well as the Hebrew words), creating new and constantly evolving performative contexts and groupings. They show us that their performance is the „gegebene Ort solcher Versuchsanordnungen„, i.e. the given site or place (Ort) for such experimental arrangements, inviting us to a laboratory experiment where the lexical and gestural components of Kafka’s texts are carefully examined, empowering the spectators to continue with their own reading ‚experiments‘ of Kafka’s writings.

At every moment and in numerous ways, the words themselves, the words that Kafka studied and wrote down in his notebook, the words he mobilized for the writing of his diaries, gradually transforming them into aphorisms and stories, are the true protagonists of the performance. The performers – the five actors and a visual artist – are the vehicles for the multidimensional performative elaborations of these words, individually and collectively creating a work of what they have termed ’speech theatre‘.

The Gallery Installations

The first part of The Hebrew Notebook takes place in an open gallery space where each of the six participants presents her or his own relatively short individual piece, consisting of a monologue or an installation. The spectators are encouraged to move around freely, exploring the different ‚exhibits‘ individually or in small groups. The two male participants, the visual artist Guy Sagi (who is responsible for the projections of the Hebrew and German ‚word images‘ in Kafka’s handwriting on the wall in the second part of the performance) and the actor Ronen Babluki present mute installations; while the three of the actresses, Shirley Gal, Tali Kark and Adi Meirovitch recite short texts by Kafka to one or a small group of listeners. The fourth actress, Yael Mutsafi impersonates Ruth Kanner, telling us how the performance that has just begun originated, after she had been asked to participate in the National Library project for its 120th anniversary celebration. There are also some short texts by Kafka glued onto the gallery-walls as well as quotes from the Walter Benjamin-essay that I referred to before, as well as the well-known photograph with Kafka wearing a straw hat, seated with two men and a woman in a mock papier-mâché airplane taken in the Viennese Prater in September 1913. Here, as opposed to most of the photographs of Kafka, he is smiling, apparently enjoying himself, while posing for the camera.

I begin with Yael Mutsafi’s impersonation of Ruth Kanner, where we learn about the director’s excitement when she was exposed to the notebook for the first time. This is how ’she‘ (Kanner/Mutsafi) begins; with a text which even in reading gives us a sense of her intonations and gestures as well as the idiosyncrasies of a Hebrew speaker (here in English):

Did you know that The National Library in Jerusalem celebrated its 120th anniversary? And towards these celebrations they made a special project – they invited 12 artists, to choose, each, an archival item from the library and to do some work with it. I went to the library. I was looking for something that would be of interest to me, but didn’t find anything. I was on the verge of giving up … and then – just like that – without any real expectations I asked the archivist – perhaps, by any chance – you do have there something hidden on… of…probably not… ‚cause everything has been published and said but… perhaps… yet… you have by any chance something in the archives of… Franz Kafka???

And he said: yes… and went underground – that is where they hide all of their special treasures in safes – and came back with a thin, blue notebook and put it in my hands!!! I am holding in my hands a notebook that Franz Kafka himself wrote! His own handwriting! I didn’t know what to do with it – I smelled it! I wanted to eat it!!!

And then, I opened it and saw a list of words in Hebrew! This was the notebook from which Franz Kafka had studied Hebrew.[16]

The performance begins by introducing the notebook with its more than three hundred words which Kafka himself had written down in both languages. This document triggered the desire of the director to smell the pages and to devour the words, transforming them into a performance that originates from and explores the materiality of the words, each with its unique qualities and taste as well as the infinite potentials for combinations with other words, creating the basis for the speech acts which gradually develop into complex stories. The notebook is an unexplored territory which has been hidden in the archives of the National Library, now revived as the point of departure for the performance we are going to experience.

After hearing about the ‚birth‘ of the performance (from the smell of the words Kafka had written down in his own handwriting) we can see and hear Adi Meirovitch present a short passage about eating from Kafka’s diary which serves as a sharp juxtaposition to the kind of appetite the notebook triggered for the director. After taking out a small piece of red candy that she is eating from her mouth, holding it in her hand, Adi begins to recite:

This craving that I almost always have, when for once I feel my stomach is healthy, to heap up in me notions of terrible deeds of daring with food. I especially satisfy this craving in front of pork butchers. I see a sausage that is labelled as an old hard sausage; I bite into it in my imagination with all my teeth and swallow quickly, regularly, and thoughtlessly, like a machine. The despair that this act, even in the imagination, has as its immediate result increases my haste. I shove the long slabs of rib meat unbitten into my mouth, and then pull them out again from behind, tearing through stomach and intestines. I eat dirty delicatessen stores completely empty. Cram myself with herrings, pickles, and all the bad, old sharp foods. Bonbons are poured into me like hail from their tin boxes, I enjoy this way not only my healthy condition but also a suffering that is without pain and can pass at once.[17]

As opposed to Yael Mutsafi’s tongue-in-cheek impersonation of the director, this is a recital of a text where the speaker establishes a critical distance from the first-person voice of the narrator in the text itself. Instead of showing us the different dishes that Kafka mentions, Adi puts the candy back into her mouth for a short while, and then takes it out again, ending the presentation by offering a piece of candy from the jar to her listeners. This is her craving; not Kafka’s.

In one of the corners of the room, while playing with a little human shaped figure, Shirley Gal recites a section from the First Octavo Notebook about a Chinese visitor who does not speak German but insists on coming to see the narrator of the story-fragment. She ends her presentation when she – as if breaking some secret taboo – suddenly takes a small bite from the figure. And while approaching Tali Kark who is hiding in another corner of the room it is possible to hear her whispering some of the aphorisms of Kafka from the Octavo Notebook, the so-called Zurau Aphorisms, including the second part of the one which I have quoted the first motto: „Es gibt ein Ziel, aber keinen Weg; was wir Weg nennen, ist Zögern.“ [There is a goal/destination but no way there; what we call way is hesitation.“] She is a fortune teller, conveying some terrible secret about ourselves. We are at a fair; like the one where the photograph of Kafka with his friends in the airplane was taken.

The two male participants employ quite different expressive means for inviting us to enter the world of Kafka’s ‚Hebrew Notebook‘. Guy Sagi sits on a chair with a sketch block on his knees drawing concentric circles with a pencil on a sheet of paper. He gradually fills the page with the circular pencil movements, perhaps like Kafka, gradually filling the pages of his notebook with words in Hebrew and German, fulfilling the cyclical patterns of history by returning to the Hebrew language; or by just creating a ‚black hole‘. He is mute, like Ronen Babluki, who during his introductory installation stands in front of a gallery wall watching a short video of himself, photographed from behind while painting a white wall with a big brush and with a bucket of paint just behind him. The live actor is standing 2-3 meters in front of the gallery wall, with his back turned to the spectators. He is holding an identical (or the same?) paint brush in his hand and to his right stands a/the bucket with paint. As the figure in the video is taking a step back to dip the brush in the bucket, so that he can continue painting, the live actor does the ’same‘ thing, mimicking this particular act in the video, including scraping off the superfluous paint in the brush. But when the figure on the wall resumes the act of painting, the live actor in front of us comes to a standstill, just watching himself, continuing to paint like before. The installation is a demonstration of the creative process where the „ever-changing contexts and experimental groupings“ of Kafka’s gestures are explored in a theatrical, performative context, as Benjamin had suggested in his Kafka essay.

Fig. 2 Ronen Babluki dipping the paintbrush/es in the bucket(s). Photo: Noa Elran

In the beginning of the video installation there is a short quote in Hebrew from the opening section of Benjamin’s Kafka-essay, which in the German original is „Weltalter hat der Mann beim Tünchen zu bewegen.“[18] In the English translation the quote reads „The man who whitewashes has epochs to move.“[19] The context where Benjamin’s description of the movements of the man who is painting appears in the Kafka essay is in a comparison between Georg Lukács, who Benjamin argues thinks in terms of historical ages, while Kafka thinks in terms of „cosmic epochs“ (Weltaltern). Benjamin wants to draw a clear distinction between Lukács, who is the historical materialist, while Kafka – as Benjamin’s essay will gradually claim – should probably be termed a ‚metaphysical materialist‘. In the essay itself Benjamin has added an additional sentence, saying that „Und so noch in der unscheinbarsten Geste,“ meaning that this – having epochs to move – also goes for what in the English translation has been rendered as „his most insignificant gesture“, but is closer to „inconspicuous“ or „nondescript“ gestures. Directly after having presented the comparison between Lukács, who Benjamin quotes as having said that the carpenter who wants to make a decent table nowadays „must have the architectural genius of a Michelangelo“ (795), on the one hand, and Kafka’s whitewasher, on the other, Benjamin almost triumphantly adds that „on many occasions, and often for strange reasons, Kafka’s figures clap their hands.“ (795) Here however, while for Benjamin the association leads to the figures clapping their hands, Ruth Kanner and Ronen Babluki compress the image of whitewashing (including its political dimensions) into a mute installation depicting these epochs of time in front of an empty wall.

‚Kabbalat Mila‘

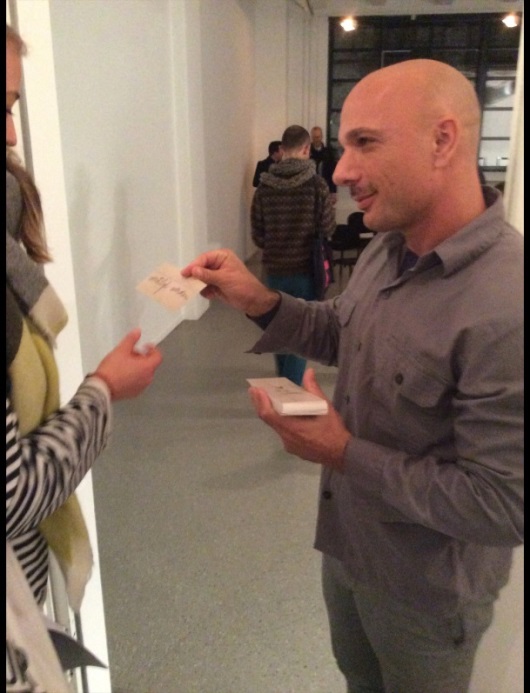

Prior to the beginning of the introductory section outlined above, one of the actors shortly explains what the procedures of the event we have just joined are. We are first told that we will be able to see all of the introductory installations if we follow certain rules of time-keeping, creating a mock-educational dimension of the performance, but without any irony. We are also told that at a given sign the preparatory stage of the introductions will end and we will pass through the ‚Kabbalat Mila Ceremony‘ in order to enter the space where the „performance itself will take place“. This very simple ceremony which involves each and every one of the spectators but only takes a few minutes reinforces the ‚educational‘ context the performance. In the ceremony one of the actors presents a little grey card with a word from the notebook, in Kafka’s handwriting – in Hebrew on one side and in German on the other – to each individual spectator as we are about to pass through the door leading to the more traditional performance space. Each spectator gets her or his own individual word. This again draws attention to the materiality of the words on the pages of the notebook. These cards could even be used as flash-cards for studying Hebrew or German. It is even possible that they are part of a lottery or some kind of puzzle which we will be introduced in the next room.

Fig. 3 Ronen Babluki giving a word-card to one of the spectators in the Kabbalat Mila ceremony. Photo: Kineret Kisch

Kabbalat Mila, the name for this seemingly simple ceremony – the rite-de-passage from the gallery presentations to the inner performance space – literally means ‚Receiving the Word‘. But this direct, straightforward name evokes an ambivalent tension between the names of two ceremonies which is only exists in Hebrew. The first is Kabbalat Shabbat, the ceremony for greeting the day of rest on Friday evenings. Kabbala, besides meaning receiving or acceptance, is at the same time also the mystical teachings of Judaism, where letters and words contain numbers which can reveal hidden secrets about a person’s life or about the Godhead. And the second ceremony which is evoked by the strange collocation of Kabbala and Mila is the Brit Mila, the circumcision through which the Jewish male child is brought into the covenant between God and Abraham (Genesis 17:10-14) when he is eight days old. But the word mila, though from another lexical root, also means ‚word‘. Thus, playing on the double meanings of mila, the Hebrew ‚word‘ (for itself) becomes directly connected to the circumcision and the covenant between man and God, made by using words in the same language in which the world was supposedly created. Studying Hebrew as Kafka did and which we are about to do, studying Kafka’s Hebrew notebook is an initiation into the work of Kafka through the art of story-telling.

Inside the Performance Space: The Classroom

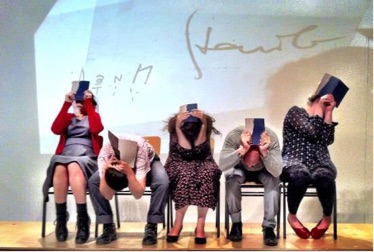

After the spectators have entered the more traditional performance space and are seated on the chairs facing a small elevated stage on which there are five chairs and with a small table standing on the floor to the left, the actors enter – each by her- or himself – showing their hesitation and formality while collecting the blue booklets from the table and finding the way to their designated chairs on the elevated stage. As pupils entering a classroom on the first day of school they refrain from looking at each other and after they are finally seated on the stage they begin to recite the words in the notebook – beginning with ‚mabat‚/gaze – presenting the strange words in Kafka’s notebook to the spectators. As they finally find the courage to utter the word ‚mabat‚ they have already acted out a whole event without looking at anyone of their fellow actors, as they are watched by the audience, establishing the spectatorial gaze.

Fig. 4 The pupils are learning the word „stam“ (unbestimmt, the second word in the notebook. Photo: Daniel Tchetchik

After a long sequence of reading, reciting, even singing many of the words from the notebook, individually and in unison, there is somewhat longer pause and Adi Meirovitch begins reciting a fragment from the Third Octavo Notebook which begins, „There was once a community of scoundrels…“ It is followed by a fragment from the Second Octavo Notebook beginning „At last our troops succeeded in breaking into the city through the southern gate…“ which is recited by Ronen Babluki while the other actors are accompanying the recital with strange sounds, and they resume the recital of words from the notebook in order to restore the ‚order‘ it represents. After finishing these readings Shirley Gal collects the notebooks and begins to recite the conjugations of the Hebrew verb radaf meaning ‚chase‘ or ‚pursue‘ in English, using the textbook The language of our people by Moshe Rat. After finishing this exercise, she begins telling the story An Old Manuscript which was written in 1917 and published in 1919 in the collection of short stories, A Country Doctor. It is followed by Jackals and Arabs which was first published in 1917, and was also included in the same, 1919-collection of short stories. Now Tali Kark leads the recital of the story, again with the participation of the whole ensemble. Throughout, the words in Kafka’s handwriting are projected on the wall behind them.

In this section, with which the performance ends, we gradually realize that the strategies of spectator attention have to change as we are transported from the world of the individual words of the notebook and their associative potentials to the disturbing narratives of conflict where the ’same‘ words now serve the development of the story. The power of the individual words is still very much present through the musicality of the collective story-telling techniques, but the disturbing, even uncanny characteristics of the situations, with the performers on the same ‚classroom‘ platform as before enact in a sketch-like manner, begin to take over. The previously more or less disciplined ‚pupils‘ are now much more openly oscillating between the position of story-tellers and nameless ‚characters‘, enabling us a quick glance into Kafka’s stories which now comment, but only as a distant, hazy or blurred reflection, on the present day conflicts in Israel.

Photo: Daniel Tchetchik

This shift to this more anarchic, dissonant form of presentation reflects the stories themselves, which both exemplify one of Kafka’s major literary themes which in turn also reflects one of his frequently repeated narrative devices: to begin the story with the entrance of an unknown stranger. This is obviously how The Trial begins, but in An Old Manuscript the intruder is not an individual but a more or less unidentified collective and the story depicts a situation which has the characteristics of a military invasion. We hear how the invaders strip the inhabitants of the town of their possessions, and we see how two of the ‚local‘ women are approached by the strangers and stripped them, leaving them in their underwear. While both of them take out a long braid of blond hair hidden from their remaining garments, attaching this braid to her much darker hair, they hesitantly recite two words, fragmentary echoes from a more optimistic past: moladeteinu (our homeland) and leshoneinu (our language).

Jackals and Arabs which is the final story of the performance also depicts an invasion, but at the same time as it is the storyteller who is the invader or just a visitor to a foreign country, the jackals say they have been waiting for him in order to help them – the animals living in this desert – to curb the Arabs with whom the stranger is travelling and with whom they, the jackals have an ancient conflict; „We want cleanliness, nothing but cleanliness“ they howl before asking the stranger to „cut their throats with a pair of scissors.“[20] The performance ends with the description of the jackals that the Arab leader of the caravan communicates to the storyteller as they are about to leave their resting place for the night in the oasis: „You’ve seen them. Marvelous creatures, aren’t they? And how the despise us!“ (39) (Gesehen hast du sie. Wunderbare Tiere, nicht wahr? Und wie sie uns hassen!)[21] This pronouncement which has been interpreted as Kafka’s skepticism towards Zionism, now also refers to the ongoing and gradually increasing racism of Israeli Jews towards the Palestinians. And after the recital of Jackals and Arabs, in the silence and emptiness that hovers over the stage as we learn about the hatred of the Jackals who have invaded the territory of the Arabs, the performance returns one more time to the notebook, creating closure with the words hashrasha (rooting) and geza (גזע race), and ending with hofa’a (הופעה appearance, performance).

Photo: Daniel Tchetchik

- Without the long and ongoing exchange of ideas with Ruth Kanner it would not have been possible for me to write this article. I want to thank her for inspiring my research as well as from a more practical perspective, for providing me with her own sources of inspiration as well as giving me crucial keys to her Kafka performance. My warm thanks also go to the marvelous actors of the group. And I want to thank Dr. Stefan Litt from the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem and Margaret Czepiel from the Bodleian Library in Oxford for their assistance. ↑

- Kafka, Franz: Zurau Aphorisms, # 26, http://gutenberg.spiegel.de/buch/franz-kafka-aphorismen-166/1 (last accessed Oct 7, 2016) „There are innumerable hiding places and only one salvation, but the possibilities of salvation are as numerous as the hiding places. There is a destination but no way there; what we refer to as way, is hesitation.“ The Zurau Aphorisms, trans. Geoffrey Brock & Michael Hofmann (New York: Schocken, 2006) ↑

- Benjamin, Walter: „Franz Kafka: Zur zehnten Wiederkehr seines Todestages“, Gesammelte Schriften, Frankfurt am Main, II, 1, 1977, 418. „/…/Kafka’s entire work constitutes a code of gestures which surely had no definite symbolic meaning for the author from the outset; rather, the author tried to derive such a meaning from them in ever-changing contexts and experimental groupings. The theatre is the logical place for such groupings.“ Walter Benjamin, „Franz Kafka: On the Tenth Anniversary of His Death“, Selected Writings, vol 2, 1927-1934, ed. Michael W. Jennings, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1999, S. 801. ↑

- In the original Hebrew: מחברת העברית – וסיפורים אחרים מאת פרנץ קפקא ↑

- The notebook was deposited in Israel National Library (Schwad 01 19 268) by the Schocken family in the early 1990’s. There are five additional Hebrew notebooks in the Bodleian Library in Oxford. ↑

- http://www.ruthkanner.com/en/Content.aspx?t=10&p=3&iid=14&eof (Last accessed March 23, 2016). ↑

- http://www.ruthkanner.com/en/Content.aspx?t=10&p=&iid=7&eof I have followed the work of Ruth Kanner throughout her career and together with Daphna Ben-Shaul we organized a ’shift‘ presenting the work of the Ruth Kanner Theatre Group at the Psi #15-conference in Zagreb in 2009, which we later summarized in writing in: „Capturing Moments of Misperformance: ‘Local Tales’“, in: Performance Research, 15 (2), 2010, S. 66-73. See also Ben-Shaul, Daphne: „Ideology of Form in Storytelling Theater: The Politics of Inter-medial Adaptation”, in: Discovering Elijah, A Play about War. Gramma, Journal of Theory and Criticism 17 (2009), S. 165-182 and Ben-Shaul, Daphna: „Her Role as a Storyteller: On Theatre Creator Ruth Kanner,“, in: Motar 12 (2004), S. 107-118, (Hebrew). ↑

- In the Frankfurt performances many more words in German were recited. ↑

- http://www.mfa.gov.il/mfa/foreignpolicy/peace/guide/pages/the%20balfour%20declaration.aspx (Last accessed March 23, 2016). ↑

- See the letter from Gershom Scholem (in Jerusalem) to Franz Rosenzweig (in Europe) from December 1927 which opens by saying that „This country is a volcano! It harbors the language! One speaks here of many matters that may make us fail. More than of anything else we are concerned today about the Arab. But much more sinister than the Arab problem is another threat, a threat which the Zionist enterprise unavoidably has had to face: the ‚actualization‘ of Hebrew.“ Quoted from Cutter, William: „Ghostly Hebrew, Ghastly Speech: Scholem to Rosenzweig, 1926“, in: Prooftexts, 10, 3, 1990, S. 413-433, hier 417. ↑

- For a critical analysis of this legal dispute and its implications for understanding of Kafka’s view of Zionism, see Butler, Judith: „Who Owns Kafka?“, in: London Review of Books, March 3, 2011, S. 3-8 (http://www.lrb.co.uk/v33/n05/judith-butler/who-owns-kafka last accessed March 24, 2015). ↑

- For a discussion of the ‚meeting‘ between German and Hebrew on the page of a Yehuda Amichai-manuscript see, Rokem, Na’ama: “ German–Hebrew Encounters in the Poetry and Correspondence of Yehuda Amichai and Paul Celan“, in: Prooftexts, 30, 1, 2010, S. 97-127. ↑

- Amenu, Sefat: Lehrbuch der Hebräischen Sprache für Schul- und Selbstunterricht, Wien 1917.משה ראטה, שפת עמנו: ספר להוראת הלשון העברית, דקדוקה וספרותה לבתי ספר ולתלמידים, וינה, 1917. ↑

- See Suchoff, David: „Franz Kafka, Hebrew Writer: The Vaudeville of Linguistic Origins“, in Nexus: Essays in German Jewish Studies, eds. William Collins Donahue, Martha B. Helfer, Volume 1, Camden House, New York 2011, S. 137-152. ↑

- See note 2, above. ↑

- From Ruth Kanner’s private archives. ↑

- Kafka, Franz: Diaries 1910-1923, (30 October, 1911), ed. Max Brod, New York 1976, S. 96. [„Dieses Verlangen, das ich fast immer habe, wenn ich einmal meinen Magen gesund fühle, Vorstellungen von schrecklichen Wagnissen mit Speisen in mir zu häufen. Besonders vor Selchereien befriedige ich dieses Verlangen. Sehe ich eine Wurst, die ein Zettel als eine alte harte Hauswurst anzeigt, beiße ich in meiner Einbildung mit ganzem Gebiß hinein und schlucke rasch, regelmäßig und rücksichtslos, wie eine Maschine. Die Verzweiflung, welche diese Tat selbst in der Vorstellung zur sofortigen Folge hat, steigert meine Eile. Die langen Schwarten von Rippenfleisch stoße ich ungebissen in den Mund und ziehe sie dann von hinten, den Magen und die Därme durchreißend, wieder heraus. Schmutzige Greislerläden esse ich vollständig leer. Fülle mich mit Heringen, Gurken und allen schlechten alten scharfen Speisen an. Bonbons werden aus ihren Blechtöpfen wie Hagel in mich geschüttet. Ich genieße dadurch nicht nur meinen gesunden Zustand, sondern auch ein Leiden, das ohne Schmerzen ist und gleich vorbeigehn kann.“ http://gutenberg.spiegel.de/buch/tagebucher-1910-1923-162/3 (last accessed October 10, 2016)]. ↑

- Benjamin, Walter: Gesammelte Schriften, II, 1, Frankfurt am Main 1977, S. 410. In Hebrew: נצחים חייב האיש להניע כשהוא מסייד. ↑

- Benjamin, Walter: „Franz Kafka: On the Tenth Anniversary of His Death“, in: Selected Writings, vol 2, 1927-1934, ed. Michael W. Jennings, Cambridge/Mass. 1999, S. 795. ↑

- Kafka, Franz: „Jackals and Arabs“, in: A Country Doctor, translated by Siegfried Mortkowitz, Prague 2015, S. 37. ↑

- http://gutenberg.spiegel.de/buch/franz-kafka-erz-161/19 (last accessed October 9, 2016). ↑